Beijing: 1# Chaoqian Road, Science Park, Changping District, Beijing, China

Shanxi: 5-1#, Zone 2, 69 JinXiu Avenue, YangQu, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China

North Region: +86-10-18515571376

South Region: +86-10-18515571396

Applications of CO2 Lasers in the Photovoltaic Cell Industry

Laser technology serves as an effective means for reducing costs and enhancing efficiency in the photovoltaic cell industry. It demonstrates significant advantages over traditional methods in various processes, including etching, grooving, doping, repairing, and metallization. The application of laser technology presents vast potential for development across different battery technologies, paving the way for further innovations and improvements in solar energy production.

1. Applications of Laser Technology in PERC Cells:

Laser technology plays a crucial role in the PERC cell sector, encompassing processes such as laser doping (Selective Emitter, SE), laser ablation, and laser scribing. Laser ablation and doping have become standard techniques, while other niche applications include laser MWT (Metal Wrap Through) drilling and LID/R (Light-Induced Degradation/Repair).

2. Applications of Laser Technology in N-Type Cells:

The use of laser technology in N-type cells encompasses laser doping, laser repair, laser etching, and laser transfer, with the potential for value growth expected to multiply compared to the PERC era. Consequently, the ramp-up of N-type cell production will significantly expand the market for photovoltaic laser equipment.

TOPCon: Laser doping enhances efficiency and is anticipated to become a standard process.

In the production process of TOPCon cells, laser technology can be utilized in selective re-doping (SE process) and laser transfer applications.

HJT: Laser repair can reliably maintain efficiency gains.

Heterojunction (HJT) is a unique PN junction formed by the deposition of amorphous silicon onto crystalline silicon, classified as a type of N-type cell. The application of light in HJT cells includes laser repair for LIR and laser transfer.

IBC: Laser grooving effectively addresses challenges in IBC cell fabrication.

IBC cells can be combined with various technologies, including HJT, TOPCon, and perovskite, to unlock significant efficiency potential. The key processes for IBC cells involve creating interdigitated P and N regions, developing superior surface passivation layers, and metallization.

Currently, laser grooving technology is primarily applied in 1) IBC cells for Etching masks and fabricating cross-finger structures in the PN junction; 2) PN region isolation; 3) Passivation layer grooving.

Laser grooving allows for the cost-effective fabrication of PN junction structures. A critical issue in IBC cell processes is the creation of spaced interdigitated P and N regions, along with achieving optimal surface passivation and metallization. This addresses current challenges in IBC technology, such as the need for multiple masking steps, which complicate the process, and the risk of leakage between PN electrodes. By utilizing laser etching, the masking step can be bypassed, enabling more cost-effective PN region fabrication and allowing for flexible and precise removal of passivation layers to form metallized contact areas.

Furthermore, laser grooving can be applied for isolating the PN regions in IBC cells. To prevent short circuits, isolation between the P and N regions at the back of the XBC cell is often necessary. Various methods for PN region isolation exist, including the use of undoped amorphous silicon to prevent direct communication between P-type and N-type doped areas, or applying laser grooving between these regions for effective isolation.

Additionally, laser grooving can be implemented in the etching of contact structures after the formation of the passivation layer and before the onset of metallization in IBC and TBC cells. The purpose of laser grooving the passivation layer is to open windows on the back of the N-type monocrystalline silicon wafer, allowing electrodes to be connected from the N and P regions for metallization. The back passivation layer in back-passivated cells typically consists of aluminum oxide and silicon nitride, aluminum oxide and silicon oxide, or doped polycrystalline silicon and silicon oxide. The thickness of the aluminum oxide generally ranges from 5 to 20 nm, while silicon nitride ranges from 70 to 220 nm. Commonly, the aluminum oxide thickness is around 10 nm, with silicon nitride between 70 and 100 nm, resulting in a light blue appearance for the back passivation layer; some manufacturers enhance the surface passivation effect by incorporating polishing processes, achieving a higher light reflectivity in the visible spectrum compared to other wavelengths.

3. Laser Transfer: A Versatile Metallization Technology with Significant Cost Reduction Potential

3. Laser Transfer: A Versatile Metallization Technology with Significant Cost Reduction Potential

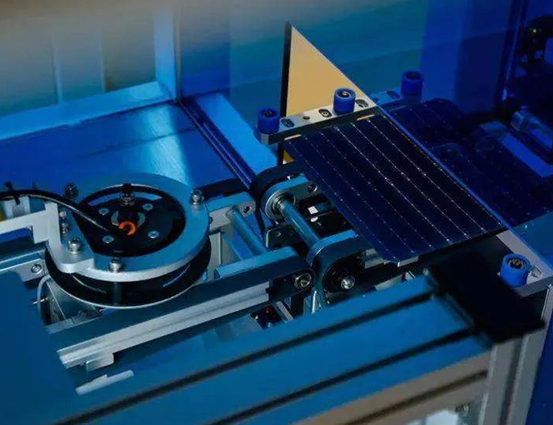

Laser transfer is an innovative non-contact metallization technique applicable to all types of solar cells, including PERC, TOPCon, HJT, and IBC. Electrode metallization is a critical process for fabricating solar cell electrodes and is essential in photovoltaic cell manufacturing. While various methods exist for electrode metallization, the current mainstream approach is contact-based screen printing. The industry is actively exploring the industrialization of new metallization methods, such as laser transfer and copper plating, to further reduce costs and enhance efficiency in solar cell production.

Laser transfer presents significant advantages over screen printing and is poised to become one of the leading technologies. The primary benefits of laser transfer compared to traditional screen printing include:

Laser transfer is a universal technology with vast potential for future industrialization. It is applicable to all photovoltaic cell metallization processes without bias towards specific cell technologies or paste types, including PERC, TOPCon, HJT, and IBC. It accommodates various paste types, such as high-temperature silver paste, low-temperature silver paste, and silver-coated copper paste. Given that N-type cells like TOPCon and HJT utilize double-sided silver paste and that the low-temperature silver paste used in HJT has higher viscosity and silver consumption, the cost of silver paste for these cells is currently significantly higher than that for PERC cells. The adoption of laser transfer can effectively reduce the silver paste costs associated with N-type cells, thereby accelerating their industrialization process.

4. Applications of Laser Technology in Modules: Thin Film Perforation and Non-Destructive Cutting/Slicing

Laser Thin Film Perforation: This technique is used for perforating double-glass solar modules. Both the front and back panels of double-glass modules require photovoltaic glass, and the back glass must be perforated at specific locations to allow the current leads of the solar cell module to be routed to the junction box. Thus, perforating the back glass is an essential step in module processing.

Currently, there are two methods for drilling holes in the back glass of double-glass modules: mechanical and laser methods. Compared to traditional mechanical methods, laser drilling offers the following advantages:

Laser Non-Destructive Cutting: This technique replaces traditional cutting methods that cause damage, resulting in no micro-cracking and lower thermal damage. It reduces efficiency loss in modules by 0.05 and is compatible with various mainstream cell types, including PERC, TOPCon, and HJT. Conventional slicing of half-cells or shingled cells employs laser thermal cutting, which forms molten grooves on the cell surface using a focused laser beam, followed by the application of an external breaking force. This method can produce micro-cracking at the cut surface and create significant thermal effects on the cell surface, potentially leading to greater efficiency losses in thinner HJT cells.

In contrast, non-destructive cutting technology can utilize separated laser irradiation or an off-axis light path to induce cracks in the solar cells that propagate and separate without causing hidden cracks. This method is expected to reduce efficiency losses at the module level by 0.05 while also contributing to improved production yields.